This month’s blog is dedicated to habit – that which can drive us to be the best we can be or drive us to total distraction. We will look at how habits are formed in the brain, why they seem so hard to break and strategies to change unresourceful habits into new, more resourceful ones.

Feature Article – Changing the Habits of Habit

Habits habits everywhere, some good, some bad, all well engrained. From the time the alarm goes off or little people start invading your bedroom, to getting up, getting showered, getting dressed, getting breakfast – all of these daily practices can be considered habit.

We need habit. Can you imagine the above routine having to be planned and thought out each day anew? You would be exhausted by the time you got to work!

According to investigative journalist Charles Duhigg, author of ‘The Power of Habit’, habits can be defined as “the choices that all of us deliberately make at some point, and then stop thinking about but continue doing, often every day”.

The question therefore is – if we are spending almost half of our time in habit mode – what are our habits doing for us? What results are our habits delivering and are they the results we are seeking? Are they taking us towards where we want to go or are they like stealth experts that sneak up upon us unknowingly and spookily hijack our day?

When it comes to our brains and habits, are they our friend or foe? The answer is both. Our brains don’t differentiate between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ habits, whatever we consistently and repeatedly do becomes embedded so that it turns into automatic behaviour.

How Habits are formed in the Brain

Our brains are efficiency machines and they create habit to save energy and reduce or eliminate unnecessary thinking time. This is why they are so hard to break as our brains take the path of least resistance. Creating new or changing existing habits is really hard work for the brain.

The good news is that once we understand how habits form, then we are well on the way to being able to change them permanently.

In our brains we have 86 billion neurons and each neuron is capable of making 10,000 connections with other neurons across a gap called a synapse (see image above). Chemicals called neurotransmitters are released whenever we perform an action or learn something new and the neurons ‘fire’. At any one time we can have around a quadrillion synaptic connections firing off – that’s more connections than there are grains of the sand on the earth or stars in the Milky Way!

The more this firing happens, the stronger the connection becomes until, after being repeated so many times, it becomes automatic i.e. a habit is formed. Habits are hard to break because they are so strongly wired into our brains. Hebb’s Law states that ‘neurons that fire together wire together’. Essentially, what this means is that when groups of nerve cells (or brain regions) are repeatedly activated at the same time, they form a circuit and are ‘locked in’.

How long does it take to form a new Habit?

Forget the 21 day golden rule, according to researchers from University College London, there is no one standard time period for a habit to form; it can take anywhere from 18 to 254 days (how specific!). The period of time depends on the level of commitment of the individual and the difficulty of the activity being learned. For example, it’s easier to train yourself to drink an extra glass of water each day than to do 30 minutes of intensive exercise. On average though, those wanting to create a new habit usually succeed around the 66 day mark as by this time the repeated practice of activities results in behaviours becoming as automatic as they will ever be.

Forget the 21 day golden rule, according to researchers from University College London, there is no one standard time period for a habit to form; it can take anywhere from 18 to 254 days (how specific!). The period of time depends on the level of commitment of the individual and the difficulty of the activity being learned. For example, it’s easier to train yourself to drink an extra glass of water each day than to do 30 minutes of intensive exercise. On average though, those wanting to create a new habit usually succeed around the 66 day mark as by this time the repeated practice of activities results in behaviours becoming as automatic as they will ever be.

Why is it SO difficult to change our Habits?

Once our neural habit circuitry is established, the brain areas involved in the circuit automatically respond in the same way every time a similar situation is encountered. This in turn leads to the circuit becoming stronger and more and more re-enforced. Such a process is crucial to learning, for example riding a bike, however it can also be associated with bad habits like overeating or reaching for the bottle when we are stressed.

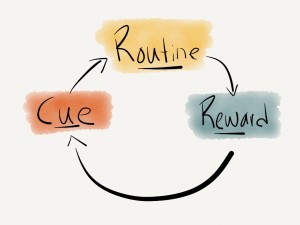

Analysing the Process of Habit with the Habit Loop

From ‘The Power of Habit’ by Charles Duhigg (reproduced with permission)

From ‘The Power of Habit’ by Charles Duhigg (reproduced with permission)

When we act out a habitual behaviour, first there is the cue or trigger followed by the routine or behaviour itself, then a reward which is how our brain learns to remember this pattern for the future. Without a reward there is no incentive to create a habit and we are often not consciously aware of the reward.

So this morning you may have looked at the clock then jumped into frenzy mode to get yourself or your little people to where they need to get to and, when you arrive on time or drop them off and arrive at work on time, there’s a sense of accomplishment.

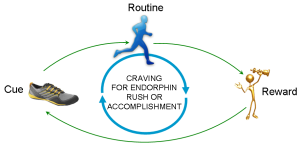

Let’s look at the habit of running or jogging

Your cue might be grabbing your running shoes or being aware of a particular time of day, you go for the run and how do you feel afterwards? Usually pretty good. I don’t really like running but I LOVE the feeling afterwards and now that I use a running app I’m getting hooked on personal bests.

Your cue might be grabbing your running shoes or being aware of a particular time of day, you go for the run and how do you feel afterwards? Usually pretty good. I don’t really like running but I LOVE the feeling afterwards and now that I use a running app I’m getting hooked on personal bests.

The reward could be how energised you feel, having time out or training for a fitness or health related goal.

Work-based Habits

There are many habits we fall into at work, not all of them helpful for our performance or productivity. Let’s look at the habit of distraction.

You’re busily working on a really important piece of work and that little email notification box pops up in the corner – what do you do?

You’re busily working on a really important piece of work and that little email notification box pops up in the corner – what do you do?

Can you easily ignore it regardless of who it’s from and what the subject title is? Do you already have it turned off to minimise distraction or do you secretly enjoy this little diversion?

It’s perfectly normal – there’s a part of our brain that is continually scanning for novelty and distraction and is in battle with the brain’s executive function or CEO. This habit is more fondly known as ‘Bright Shiny Object Syndrome’.

The cue or trigger is the pop up box

The behaviour or routine might be choosing to open it

The reward may be that you’ve cleared it from your screen and therefore it’s a sense of accomplishment or that you’ve satisfied your curiosity and given your brain a little hit of dopamine, one of our happy hormones.

How to change a Habit

When it comes to the habit loop, the part you are looking to address for successful habit change is the routine. Let’s analyse a non work related habit first – one that I am fairly familiar with, of wanting to have a drink midweek.

Step 1 is to identify the Trigger through Self-reflection.

To help identify the trigger ask yourself:-

What time is it?

Where am I?

Who am I with?

What was I just doing?

How am I feeling?

For example – It’s 7pm, I’m at home on my own and I’m at a bit of a loose end. There’s nothing interesting on the TV and I’m tempted to crack open that bottle of Shiraz that seems to be calling me, but I’m trying to break the habit and not drink during the week.

Step 2 is to identify the Real Reward

What is it I’m really wanting? Is it really the wine or is it that I want to feel less bored and more engaged? What could I do as a different routine that can still provide this reward?

Step 3 is to try a different Routine

I think I’ll call my friend for a catch up, the one whose really into health and fitness or I’m going to pick up that inspiring book I keep telling myself I’ll get round to some day or I’m going to pour a lovely refreshing sparkling water with a twist of lime into a wine glass and enjoy the ceremony without the damage! I tried all of them and the last one was the one that worked, I still wanted the ‘ceremony’.

Let’s look at a work related habit. Let’s say it’s someone else and not you but that ‘Fred’ often turns up late for meetings.

Step 1

What time is it? 20 minutes before the meeting

Where am I? at my desk

Who am I with? no-one

What was I just doing? a challenging piece of work

How am I feeling? engrossed

Fred in his self-reflection has realised that he doesn’t turn up late when he’s doing ‘basic’ work but tends to get lost in more challenging tasks which results in him being late for meetings.

Step 2

What reward is Fred really seeking? Possibly more time to complete this piece of work and he sees the meeting as getting in his way, he’s not motivated enough to stop what he’s doing and prepare for the meeting but he knows how much this irritates his colleagues.

Step 3

Fred decides to change his ‘to do’ list around and schedules in non-important work at least 30 minutes before planned meetings. He also sets a countdown alarm to go off 15 and 10 minutes before the meeting so he can prepare himself and show up physically, mentally AND on time.

Making habits stick

1. It has to be important

If we want to change a habit because someone else is encouraging us to do so and it’s not important to us, there’s not much chance we’ll succeed. We see this with weight loss and smoking cessation all the time. If we want to create a new habit we have to align it with what’s important to us, with our values.

One way of doing this it to take ourselves into the future and create a visual of what we want to be or how we want to act. We can also create a picture of the future that looks at the consequences of NOT changing our habits.

In Fred’s case he could look at how changing his ‘tardiness’ habit can help him progress in the company and work towards being a better leader. He can also see the relief and welcome looks on the faces of the other attendees as they no longer have to wait for him.

2. Set Implementation Intentions (a.k.a. ‘when….then’ Goals)

We can wish and desire to change habits ’till the cows come home but unless we take purposeful action our brains will default back to the status quo. Setting implementation intentions trains your brain in a stimulus response mechanism and, when repeated, soon becomes automatic.

Examples of work-based implementation intentions include:-

- When I turn off my laptop, I’ll create tomorrow’s ‘to do’ list

- When I turn on my laptop I’ll prioritise my ‘to do’ list

- When the alarm goes off, I will prepare for the meeting

- When I notice that I’m feeling distracted/hungry/bored etc. I will get up and stretch/walk around the block/change tasks etc.

3. Believe that it’s possible

We have to BELIEVE that we can change existing habits. This is where so many habits fall apart because we go in wishing and hoping rather than believing and end up with a PhD in ‘gonnaship’.

Alcoholics Anonymous was founded by a religious person who incorporated belief into the AA strategy. Researchers later realised that their success lay in helping people believe in something greater (not necessarily God) that could help them stay on track. IN addition, they created a support buddies framework.

4. Create a support framework

When it comes to changing habits, having support makes things so much easier. Who could be your accountability buddy? I know I couldn’t succeed half as well in developing good habits as I currently do without the support of appointed peers.

5. Make the hard stuff easier and the easy stuff harder

Shawn Achor, author of ‘The Happiness Advantage’ talks about making it harder to do that which your brain wants to default to and helping yourself by making it easier to do the new practice. For example, he wanted to go for a run when he got home instead of watching TV so he hid the batteries to the remote and had his running gear ready in the lounge.

From a work perspective there are simple strategies to manage distractions, for example, keeping only the application that you are working on open so as to beat ‘bright shiny object syndrome’.

A habit I slipped into was always saying yes when someone knocked on my office door and said, “Got a minute?” This is a complete productivity killer! It’s easier to say yes but doesn’t help us in our productivity. It’s harder to say no and can come across as dismissive. We can however offer choice and at the same time educate our team members in valuing time. “Yes of course, I can offer you literally a minute of time with limited attention now, or we can meet later for longer and you’ll have my undivided attention. Which would you prefer?”

In summary, take a moment to project yourself into two possible futures and look back, one where nothing changed and look at the consequences, and the other where you decided, committed and took action and look at the results.

In summary, take a moment to project yourself into two possible futures and look back, one where nothing changed and look at the consequences, and the other where you decided, committed and took action and look at the results.

We don’t get a second go, so when would now be a good time to change the habit of habit?

Have a clear plan

Align actions with goals & values

Believe that change is possible

Identify the cue, routine, reward

Try different rewards then change the routine

Start small and celebrate every little success